Amazon Go: We’re All F*cked - The Implications of Automated Storefronts

Amazon Go: We’re All F*cked - The Implications of Automated Storefronts

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Hannah White

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

If you haven’t heard, Amazon just launched a promo for a storefront that sells meal kits and grocery basics with no checkout lines. It’s based in Seattle and currently open to Amazon employees, with the public launch set for early 2017. While Amazon hasn’t explained their “Just Walk Out” technology that powers the storefront, they do provide a video of the charming shopping experience that will leave you wishing your local grocery store was an Amazon Go.

Amazon Go is Amazon’s attempt to grab a foothold in the grocery industry. Even with Amazon Pantry, Amazon only controls 1% of the $800 billion US market. This is because the grocery market “has stubbornly stayed offline,” according to Sucharita Mulpuru, the Chief Retail Strategist at Shoptalk. From grocery delivery companies like Peapod to meal kit delivery companies like Blue Apron, no one has been able to corner the online market or upset the titans of the grocery industry yet.

There is a list of reasons e-commerce groceries have failed to gain traction. Some people like to pick up and squeeze their produce in-person before buying it. Others want to see the cut of meat they’re getting at the deli counter. People who live alone have shorter shopping lists that don’t always justify an online order. There’s also an issue of time sensitivity: if someone needs their groceries today, they won’t be ordering them online.

When it comes down to it, the user experience of the grocery store is difficult to digitally recreate.

So how does Amazon compete with Walmart and Safeway if they can’t gain traction online?

They build a supermarket storefront that incorporates popular online products like meal kits, provides basic staples like produce and meat, and creates a user experience that rivals the Apple Store. Amazon took the experience of grocery shopping and turned it into a design problem, where the default answer — making grocery shopping an online experience — was ignored in favor of identifying and solving the problems users encounter while shopping in-person, like long lines. They also incorporated aspects of online grocery shopping that people enjoy, like meal kits, into their solution.

Amazon has taken a common chore, grocery shopping, and turned it into a novelty of technological innovation and an experience people will enjoy. Innovation has become a common buzzword in our society, and in most cases, people should be using the word imitation. However, by resisting the default approach of imitation (e-commerce), Amazon could create an innovative experience that will integrate itself into our daily lives.

And Amazon didn’t stop there. The Amazon Go store you see in that video is just one of their prototypes. There are at least two others in the works, according to the Wall Street Journal. Two drive-through grocery stores are slated to open in the upcoming weeks in Seattle, and a proposal for a large, multifunction store with curbside pickup was also approved in November.

John Blackledge, an analyst with Cowen, claims that groceries are the “company’s biggest potential for revenue upside.” He may be right because, without a check-out line, there’s no opportunity to balk at the price of your weekly groceries.

But what does this do to our workforce? Amazon Go is a frightening proposal for cashiers, who just realized they can be replaced by an app on your smartphone. Contrary to the popular belief that truck drivers lead the American workforce, the most common job in America is a retail salesperson, with cashier coming in at close second. Both jobs, which together employ a total of 7.8 million Americans right now, are in jeopardy with “Just Walk Out” technology, which is essentially AWS for grocery stores (and dare I say it, retail stores).

This sort of abrupt end to blue-collar jobs is a common theme in automation, which Amazon just achieved without even using a robot. Driverless trucks are predicted to end 1% of jobs in America, a devastating blow when you realize that is equivalent to 2 million Americans out of work. United Technologies just made a $16 million investment in automation at their Indiana factory, which will ultimately lead to fewer jobs. Since 2000, the total number of manufacturing jobs in the US has fallen by almost 5 million (30%).

Overall, 47% of American jobs could be at risk as technology advances.

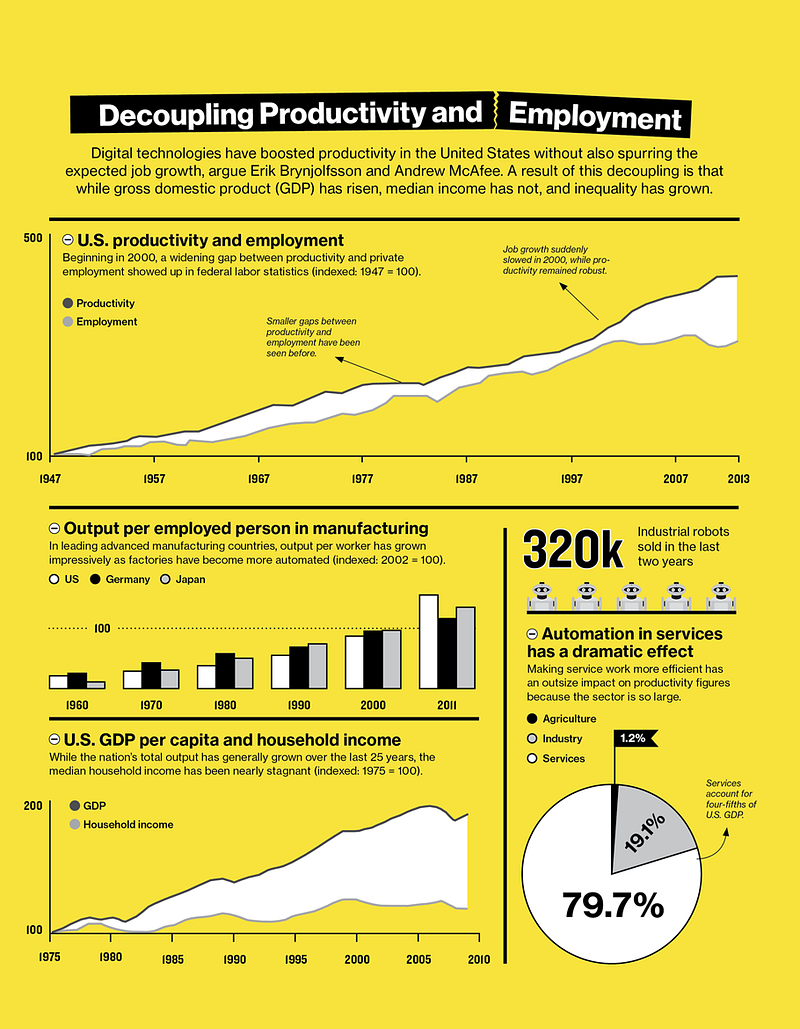

Brynjolfsson and McAfee, two MIT academics, claim that it’s not only factory and retail jobs at risk. Law, medical services, education, and financial services may all be on the chopping block as well. Rapid technology growth destroys jobs more often than it creates them. Productivity and employment steadily grew together after World War 2; businesses did well while their employees generated value. However, when we hit the new millennium in 2000, job growth slowed and the median income steadily dropped, while innovation and productivity soared. The divergence is referred to as the Great Decoupling by Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

The impact of technological advancement is more subtle when it comes to the white-collar workforce. W. Brian Arthur, a former economics professor at Stanford University, warns that it’s big data, machine learning, and digital processes that will challenge white-collar jobs. According to McAfee, “digital technologies are doing for human brainpower what the steam engine and related technologies did for human muscle power during the Industrial Revolution.” As digital technology gets “smarter”, it encroaches on human skills in new ways. The threat to middle-class jobs becomes more concrete with each advancement, inevitably worsening the economic inequality that already exists.

But if the end of work is actually near, what happens to all of the unemployed? Elon Musk believes universal basic income is the answer to automation and technology advancement. President Obama said the debate on universal basic income could be only 10 years away. One province in Canada is pushing forward with plans for a trial run of UBI already. Of course, there are those against UBI. Look no further than the National Review and Huffpost for those.

As technology rapidly advances in the Internet of Things, it’s on all of us to be conscious of how our products affect the economy and workforce. Automation, big data, and digital systems are all here to stay. The question is, how do we implement these things as a force for good and counteract the economic divide we create?

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles