Chinese IoT: The Threat Ignored by UK Politicians

Chinese IoT: The Threat Ignored by UK Politicians

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Guest Writer

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

The Chinese Communist party can congratulate itself on another sign of its rise; for the first time, it has become a factor in deciding the fate of British politics. During the televised leadership debates, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak tried to appeal to Tory members by outdoing each other on their commitment to protecting national security, economic prosperity, data privacy, and values from the CCP. They both referred to the Chinese theft of our science and technology, but the problem is much, much wider than that. What is more serious is our blithe willingness to import Chinese control into the most sensitive areas of the UK's economy and society. Neither aspiring prime minister mentioned the most crucial area – more crucial than 5G and Huawei. Our politicians have finally grasped the threat in telecoms. They may even have grasped the importance of semiconductors. But UK politicians continue to ignore the Internet of Things (IoT) and our dependence on Chinese IoT modules. There may still be just enough time to wake up.

'UK politicians continue to ignore the Internet of Things (IoT) and our dependence on Chinese IoT modules.' -Charles Parton

Why Does IoT Matter?

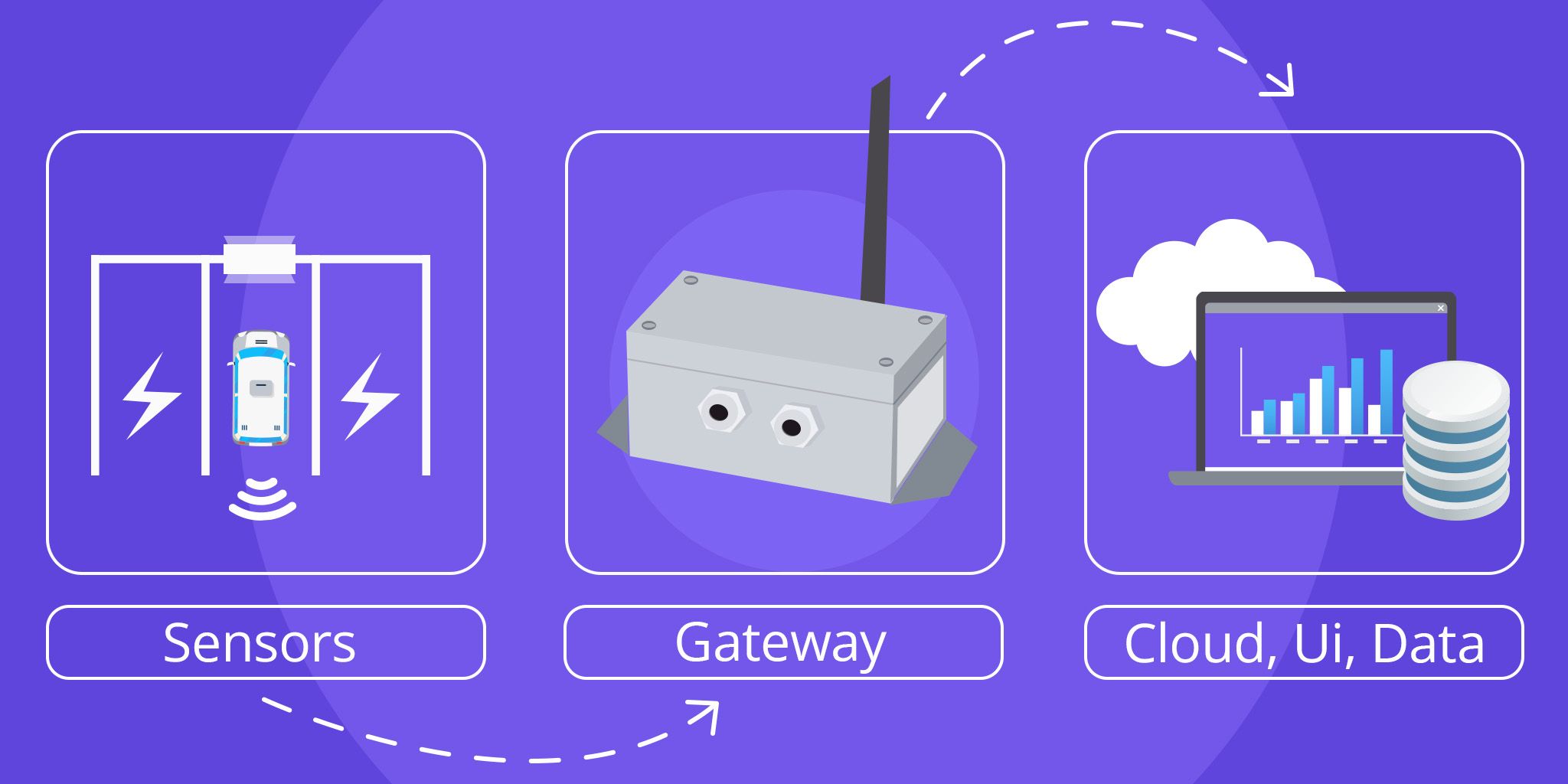

IoT is becoming the central nervous system of the global economy. It consists of a vast network of devices connected over WiFi or cellular networks. These devices are embedded with sensors, software, processors, and communication capabilities. They link up with each other to exchange and process huge amounts of data collected from their environment. They carry out tasks autonomously, at speed, and with limited human engagement. The worry is that in the CCP's hands, these modules would also allow a hostile power to monitor and control the UK’s systems.

At home, you will find IoT modules in smart meters, smart kitchen appliances, and security cameras (including in your doorbell). They are also in your car. When you shop or eat out, an IoT module may process your payment data. But maybe you do not care who has access to your data. However, others certainly do. Suppose you were a Uighur or an exiled Hong Kong democrat living in Britain. Or perhaps you work in a sensitive government or military position. Would you want the CCP to be able to trace your whereabouts, the people you meet, or even – by applying artificial intelligence algorithms to large amounts of your and others’ data – anticipate who you will meet and where?

The Far Reach of IoT

But it is outside the home that the threat is greatest. IoT spans supply chains, manufacturing, agriculture, transport and logistics, urban planning, security, and, increasingly, all aspects of human-to-machine and machine-to-machine interactions. It is embedded in our critical national infrastructure. We should hope that Chinese IoT modules would not be allowed inside any of our weapon manufacturing facilities. But have we considered the intelligence that could be gained from modules embedded in our logistics network?

As anti-tank weapons and missiles are moved around, the transport data and metadata could provide good intelligence on the likely numbers, destinations, and reserves of such systems. For example, how many have been shipped to Ukraine? Or in the case of the U.S., where are its Javelin missiles located, and how many have been sold to Taiwan?

Intent + Capability

Academics define threat as intent plus capability. The CCP has made its intent clear. As General Secretary Xi Jinping said at his first Politburo meeting in January 2013, "Chinese socialism must attain the dominant position over western capitalism." When he talks of the "great rejuvenation of the Chinese people," he means China replacing America as the top superpower and changes to global governance and systems that better suit the People’s Republic. His four main tools for achieving this are:

- Economic "sticks and carrots" diplomacy

- Massive investment in external propaganda

- Interference in other countries

- Domination of the new technologies

This last is the most important. The "Made in China 2025" and other industrial policies are backed up by methods fair but often foul. Subsidy and access to central funding, the hiring and buying of top western brains, espionage, and the unauthorized downloading of research in our universities are among the means used. If China can dominate the new technologies and the industries they spawn, it will gain immense economic – and even geopolitical power.

When it comes to capability, we could start with the paradox of incapability. As with Huawei and 5G, poor design is itself a threat. A GCHQ cell report made clear that the worry with Huawei was bad design, so bad that anyone, not just the Chinese state, stood a good chance of gaining unwarranted access. It is difficult – perhaps deliberately – to know where incompetence ends and malign intent begins. The same applies to Chinese IoT modules. American security companies had to warn of severe vulnerabilities in Chinese-made IoT GPS trackers for cars and motorcycles that "could result in a loss of life."

IoT, the Cloud, and Your Data

Even if a device is clean when installed, there will be a myriad of software updates over its lifetime. These may contain malware, and they cannot be adequately monitored. The coupling of IoT devices and the cloud is a powerful combination. One of the most attractive features of IoT devices is that the enormous amounts of data they gather can be processed at scale, and so they can provide detailed and often predictive insights into the processes – or people – being monitored. The information stored in the cloud could be used with hostile Chinese intent. The Chinese firms manufacturing IoT modules are starting to provide services that help companies use their own data. The cheapness is tempting, but storing data in China is madness. Using the cloud in one’s own country or the United States is more (although not fully) secure. And some organizations will be tempted to use cheaper services in third countries, where China may find it easier to get around security.

Chinese companies may swear that your data stays in your country. But there is scant reason to suppose that they differ from Huawei, which "unintentionally" left access into Vodafone’s systems, or from TikTok, which lied to Congress and parliament about data going back to China. Chinese producers of IoT modules go under the radar. Yet, they are a key part of an ecosystem of Chinese technologies that includes the likes of Hikvision, DJI, ZTE, and HiSilicon, as well as Huawei. All of these companies are subject to export controls in the U.S. because of their roles in helping military modernization, building surveillance and repression systems in Xinjiang, and threatening the security of free and open nations.

Three Chinese companies – Quectel, Fibocom, and China Mobile – now control more than 50 percent of the global markets for IoT modules. More concerning, they represent nearly 75 percent of the connections made by these modules. The CCP intends that they should erode and eventually eradicate western capability in this area.

Eliminating Dependency

Dependency is defeat. But the battle is not lost. In the case of Huawei, the only other western choices were Ericsson and Nokia. Fortunately, there are a plethora of western companies producing IoT modules. We have to ensure an unfettered and unthreatening supply chain. That means banning the use of Chinese IoT modules in our countries. The UK cannot ignore trade and investment with China. The CCP may be a hostile power, but interdependencies mean that we cannot cut them off completely. Just as there are areas where we are happy to co-operate, so there are also areas where national security, human rights, or other factors make sharing impossible.

Boris Johnson managed – at the 11th hour and with a little bit of help from the U.S. and clear-sighted backbench MPs – to see sense over Huawei. Judging from the prime minister debate, our new prime minister will at least recognize the threat from the CCP to our science and technology. Now he or she needs to do more homework. Requesting a briefing on IoT would be a start.

This article was first published in The Spectator on July 30, 2022.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles