Smart City Data

Smart City Data

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Susan Morrow

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Strong driving factors are behind the push to smarten up our cities. In the 21st century, we're faced with the vital need to manage the lifecycle of human day-to-day activities. We're talking here about our basic human needs: food, hygiene, waste disposal, clean air, medicine, transport and work. To create optimal conditions for many people on a small Earth, we have no choice but to be clever about it. So, what do we have to help us in this endeavor?

- We have our brains, which can, on occasion, be put to good use.

- We have the technology, which is advancing well in line with our needs to optimize life on the planet.

- We have the data that we create, each day, carrying out our human activities.

Our smart cities have to use all three factors to create a sustainable city that works, but what about the basic human need for privacy?

Trends Towards Smart

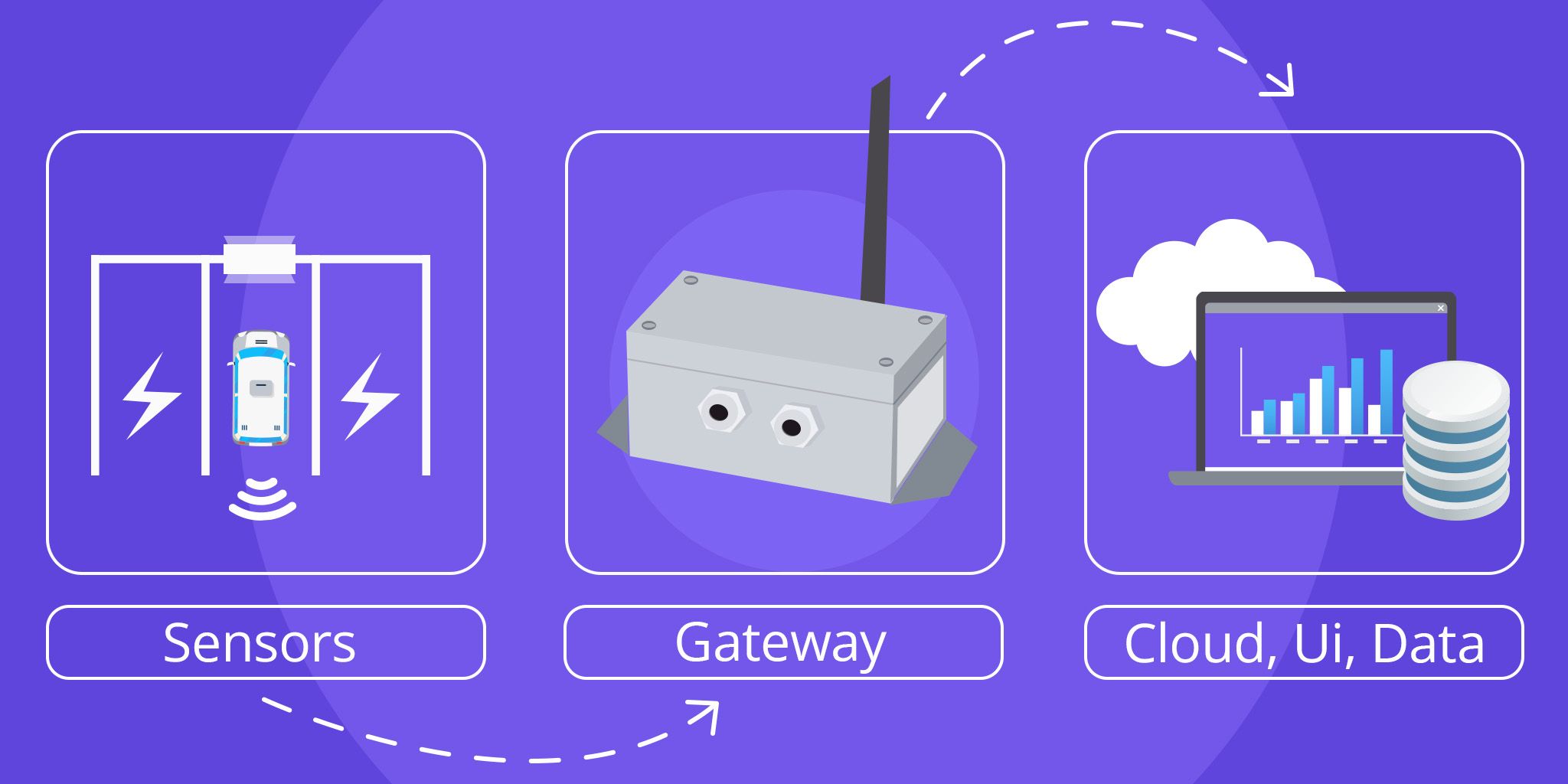

Technology is always ‘trending’ in some way or another. However, it's a mix of policy, human factors and technology that will allow smart cities to evolve. Firmly in the technology camp and crucial to this drive is the Internet of Things (IoT), big data analysis, automation, machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI). However, technology doesn't stand alone. It's the use and application of the technology that makes it effective. Governance and policy, along with factors-- such as acceptance by citizens, are as equal in importance as the technology that helps to build a smart city. If we look at the three in unison, we can see how they interact and inform each other as part of a wider smart ecosystem.

Our Smart City Privacy series explores the link between digital identity and the smart city, arguing that tying our identities to IoT devices creates a critical #Infrastructure that makes managing privacy and security difficult.

Data: The Blood of the Smart City

The idea of ‘Moore’s law’ caught everyone's imagination as we saw computers increase in power as they decreased in size and cost. The actual underlying observation was that the number of transistors on integrated circuit boards doubled every two years. Interestingly, but coincidentally, we are seeing the same thing happening with data. In December 2017, 54 percent of the world’s population (4.15 billion) were Internet users. Internet usage is never benign. The Internet has evolved into a personal data transfer system. We have online accounts for virtually every online interaction. Accounts, like banking, e-commerce, gambling and so on, each containing personal as well as behavioral data. We also each own, on average, 3.6 connected devices.

There is so much data that we have had to build new technologies to create it and analyze it. Big data is one of the phenomena of the modern age. Data, however, is not an abstract thing. Data is a representation of us, as individual humans, or as a group of humans; it can show relatedness between humans in groups. It presents a technological front that shows how we behave, how our families behave and how our friends and enemies behave.

Data used in a smart city context is a reflection of our human face and our behavior.

Big data is the lifeblood of the components that make up our smart cities. It is being hailed as the “new oil”, “like gold” and the saving grace of future technologies. However, it can also be a poison chalice. Data is only as good as the value it offers, and this value is determined by a number of things including in-built bias, its trustworthiness and the value of these data. It's also an area where governance needs to build a strong guard.

Data privacy is often an afterthought. It seems like we have to sacrifice privacy for progress. This should not be the case and does not have to be. Strong control and governance of smart city data will bring rewards in trust and respect by those citizens that data represents.

Data and Identity in the Smart City

Digital identity is also about data. The attributes that generate the identity or that are requested during an identity transaction, are the same as many IoT-linked data. And, it's our identity data that are used to setup IoT accounts, share IoT generated data with third parties and that will be linked to data generated by other smart devices in the smart city. It seems a natural progression, then, that digital identity will become intrinsically linked with living in a smart city.

Digital identity has the potential to become the literal backbone of a smart city. As the digital equivalent of you, your digital identity data can open up smart transactions and tasks.

Placing identity as an integral part of a smart city could be a dangerous thing both from a security and a privacy perspective. IoT device ownership or association is already tied to an individual. To extend this to make a persistent link with a verified digital identity is the natural next step. The data generated by that device would then be linked to that identity, going forward; it would create a history with patterns and trends. Our digital identity will become an exploded form of everything about us as IoT devices link traditional identity data like name and age to behavior and more. VR headsets are already being used to track body movements. A paper by researcher Jeremy Bailenson “Protecting Nonverbal Data Tracked in Virtual Reality”, which looks at the privacy issues of nonverbal data demonstrated how a 20-minute session using a VR headset can capture 2 million recordings of body language.

It's in the linking up of identity with devices with data with transactions that cause complex webs of privacy that are hard to resolve.

Techniques like minimal disclosure of attributes can help. Decentralized technologies such as ‘Self Sovereign Identity (SSI)’ can go some way towards decoupling identity, transaction and device. But, in the real world where attributes need to be declared to obtain services, there's no clear route yet to decoupling the web of linkable data.

Having a system that has privacy at its heart to build Privacy of Identity (PoID) focused identity ecosystems is crucial for privacy-enhanced smart cities.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles