Human Rights and IoT: The Right to Fair and Decent Work

Human Rights and IoT: The Right to Fair and Decent Work

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Hannah Sloan

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

IoT, Machine Learning, and the growth of Artificial Intelligence will continue to transform our world, bringing with them great promise and great risk. These technologies elevate the possibilities for human prosperity and innovation. However, job loss, privacy infringements, and the increasing agency of robotic systems are all acknowledged risks if not inevitabilities.

Concerns about access to work and livelihood aren't new. They echo ideas about work, power, and dignity that have emerged in different words throughout human history. In 1948, when delegates from 48 countries came together to sign the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), they sought to capture in words what a "good human life" meant. These words would serve as goals and principles to aid supranational and national governance.

Human rights provide a useful framework for analyzing the risks and ramifications of technological development; they allow us to assess whether technology is exacerbating rights violations and/or increasing rights protections. Analyzing, predicting, and proactively responding to the negative effects of the adoption of new technologies will be critical to sustaining social transition into an increasingly automated world.

An International Bill of Rights

Human rights are invoked in protest, in court, in conversation, and in the agenda of state and non-state actors across the globe. They are a normative framework—one that suggests how we should live or should think about our fellow humans—based on the idea that people are endowed with certain rights endowed by virtue of their humanity.

Many would argue that human rights were created to represent a generalized consensus among world leaders about how states should interact and how governments must function to be considered "legitimate" or functional in the contemporary world. They represent a set of broadly shared values across cultures and political systems, as well as a common standard for achievement. While these rights are not necessarily protected by any international legal system (except for violation of basic security rights, including crimes against humanity), they have been incorporated into the legal systems of numerous states. In addition, they remain an authoritative reference point when discussing the morality of different policies.

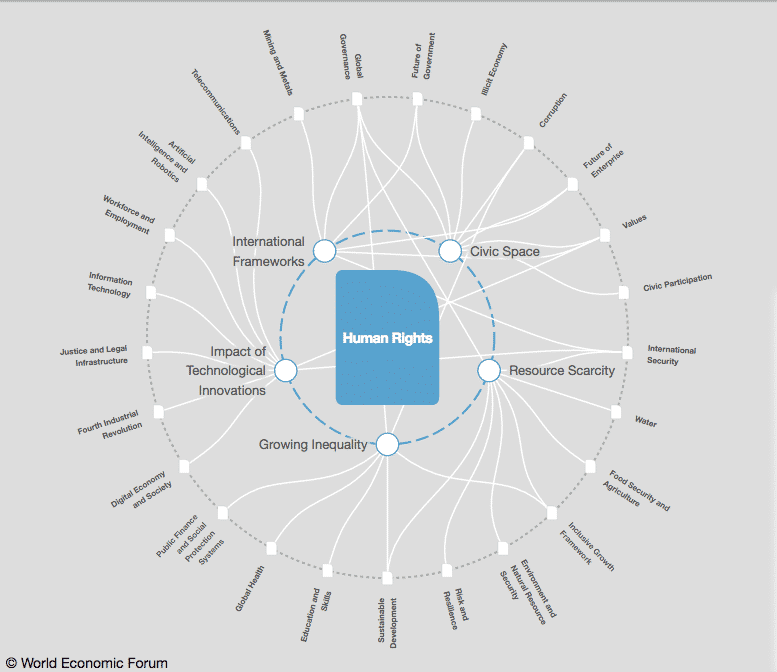

Image Credit: World Economic Forum

Human rights are theoretically interdependent and indivisible: each upheld right helps to uphold other rights, and they are all important to the wellbeing of an individual. Historically, however, the US has chosen to accept some human rights as more “legitimate” than others. In 1966, two covenants were created as addenda to the UDHR, producing what is together called the International Bill of Rights. Embroiled in political turmoil leading up to the Cold War, the US and UK advocated heavily for the strict protection of civil and political rights (e.g. the right not to be tortured, the right to a fair trial, and freedom of religion). The former Soviet Union advocated instead for the protection of economic, social, and cultural rights (e.g. the right to adequate food and housing). The two ideological blocs' different values had a lot to do with the battles they were fighting over which economic or political system was best. The way they chose to prioritize rights reflected—and still reflects—that tension. While human rights don’t dictate domestic policy, it’s inevitable that political factors motivate the creation and interpretation of human rights.

Why Use Human Rights to Frame the Risks and Rewards of Technology?

With one glance through the UDHR, the document can seem purely aspirational. Since when did the right to social security, for example, become an unalienable right? Since when did states protect that right? Many opine that human rights provide a vocabulary with which to distinguish between things that improve human existence and things that deteriorate and diminish it. While a lot of discussion about technology praises its potential to amplify human capabilities, it’s impossible to state the value of technological development without assessing how it affects fundamental human rights protections.

In the series of posts that follows this piece, we’ll explore themes in human rights that are relevant to IoT—where IoT is most likely to intersect with human rights protections and violations. In later posts, we’ll discuss concerns about privacy rights, human rights policing, disaster response, and blame for violations committed “by machines.”

[bctt tweet="#HumanRights are about what makes for a good and flourishing human life. As #automation increasingly transforms our everyday work and lives, human rights provide an important framework. || #IoT #IIoT #m2m @hb_sloan" username="iotforall"]

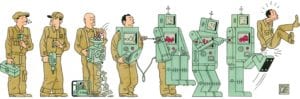

The “Right to Work” in an Automating World

It’s no secret that technological advancement and automation will destroy jobs. It’s no secret that this will happen at great scale. As powerful AI and IoT systems grow, they propagate the inevitable: the efficiencies produced by automation will result in widespread job loss. It’s entirely possible that the continued growth of constantly-improving and self-maintaining machines could eliminate 99% of all jobs today.

Because of this cynical (but realistic) prognosis, much of the debate about job loss centers less on whether it will happen and instead on how acute it will be. Future predictions aren’t entirely bleak on this front. Technology has created countless new jobs throughout history while eliminating others. In theory and in history, this rings true. Jobs leave, jobs come, and the transition is often painful.

Why should we care? 99% job loss—an unlikely prospect in the very-near but perhaps not-far-off future—is daunting because of the economic, political, and social effects of increased unemployment and workforce transition. No matter how quickly our institutions respond to train the next generation of workers, there will be difficult lag time between technological transitions in the workforce. Present threats of political instability, increasing economic inequality, and rising poverty rates have social consequences. Marginalization and discrimination can be more easily reinforced in a world in which it becomes quickly unattainable to make a decent living.

Image Credit: MIT Technology Review

Job loss is just one predicted effect of technological growth and change. Its effects are enormous in scale, but they also manifest on a personal level. Aside from seeming generally bad in the short term, job loss can be catastrophic for individuals and families—blue- and white-collar alike—who depend on work not only for income but also (relatedly) as a basis for dignity and quality of life. This sentiment is magnified here in the US, perhaps, where the capitalist “American Dream” drives (if indirectly) the cultivation of a dedicated work ethic.

Article 23 of the UDHR states:

- Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

- Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

- Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

- Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

(Don’t confuse the “right to work” with right-to-work laws in many US states, by the way. Certainly, there are related aims, but the “right to work” laid out in the UDHR refers broadly to one’s opportunity for safe and gainful employment.)

Risks of an Automated Workforce

IoT adoption, artificial intelligence, and automation more broadly will cause shocks to the global labor market. These disruptions will destroy certain industries, displace the jobs of millions of people, and leave many without access to income or adequate social protections.

A lack of previous opportunities means that people will make compromises in order to find work, increasing incentives to work in exploitative work conditions and/or under unfair employment contracts. Thus, there will be less opportunity for one to work in “free” and “just” employment schemes. There will be less guarantee—though in most countries there has never been any guarantee—of “an existence worthy of human dignity.” Unionization will be restricted by limited demand for labor. Access to basic levels of subsistence outside of gainful employment will be uncertain and unlikely given the political and economic shifts needed to accommodate these shocks with sustainable infrastructure.

It’s not controversial to be this predictive. These disruptions have been true of many technological innovations in the last decade, but the social structures in place that mitigate some of these effects are incapable of handling the exponential levels of automation and job loss that are on the horizon.

Aside from limiting opportunities for work, IoT (and automation technologies more broadly) will mechanize aspects of the hiring process itself. IoT can help collect information about prospective employees. Machine learning algorithms can make decision-making easier for employers based on a myriad of personal and professional factors. Basically, this could lead to the propagation of biases in the hiring process. There is little protection from discrimination in an automated process like this. In fact, this will only magnify and institutionalize what were before internalized hiring biases, which are more ready for checks and balances.

IoT and Potential for Human Rights Protections

Technological innovation will disrupt the global job market, but it will also transform it. With the increasing availability and reliability of sensors to track the lifecycle of production, there comes an increased capability to monitor supply chains of goods and services. When rights violations occur along the supply chain—such as the use of bonded or forced labor, or the presence of unsafe working conditions—the physical and structural intel. provided by IoT systems and machine learning algorithms will help pinpoint violations where they occur.

Technologies like blockchain, for example, can be used to validate consumer transactions and monitor supply chains for greater transparency. “Everledger uses blockchain to track the provenance of diamonds—in particular, whether or not they come from conflict zones,” writes Ruth Hicken of the World Economic Forum. “Provenance has tested tracking the origin of fish initiated by the catcher on the boat—in an industry where slavery is rife.”

Wearable technologies and other sensor data can also help monitor firm compliance with human rights treaties through investigating discrimination and workplace abuses. Participation in IoT systems will produce data that can better monitor human rights abuses and increase protections. IoT will do more to ensure that work is “just” and “free” than it will to ensure that work remains available.

As for making work available and accessible—some are optimistic that IoT will create more jobs than it eliminates in upcoming years. However, the skills required to do these new jobs are not sufficiently present in the current workforce to satisfy new demand. IoT can help here as well. Educational applications of IoT technology can result in more experimental, personalized learning for students and teachers; IoT systems can also help monitor the physical maintenance of schools to sustain safe and functional learning environments. Open-source curricula and increasingly comprehensive technical education resources will be necessary to promote quick adoption of skills the IoT industry needs.

Image Credit: ScienceSoft

The Burden of Protection

Human rights are closely tied to governance; while non-state actors (NGOs, multinational corporations, legal bodies, social movements, etc.) play the role in many countries of being “human rights agents,” the International Bill of Rights was written with the state in mind. The state government was and in most cases still is seen as the main body that can actively protect human rights and prevent violations.

Article 6 of the 1966 Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights states the following:

- The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right to work, which includes the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts, and will take appropriate steps to safeguard this right.

- The steps to be taken by a State Party to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include technical and vocational guidance and training programmes, policies and techniques to achieve steady economic, social and cultural development and full and productive employment under conditions safeguarding fundamental political and economic freedoms to the individual.

These statements use the language of the UDHR, but they place more emphasis on how states are supposed to protect these rights. Fulfilling rights protections, in this case, will require more than states not interfering in the lives of citizens. It will require vocational guidance, training, and employment services geared toward the demand for new kinds of jobs. It will also require acknowledging unpaid forms of work (e.g. care work in the home) to capture the full effects of job elimination.

Public-private partnerships (e.g. the Partnership on AI) can provide critical avenues to proactively respond to workforce disruptions in the coming decades. IoT will exacerbate these disruptions and will hopefully generate new jobs in place of those eliminated. Education and collaboration will be necessary to endure the inevitably painful workforce transition. In a world that may require less human labor, human rights provide an important framework through which we can assess desirable policies for social organization. The founding principles of human rights are concerned with what makes for a good and flourishing human life. We must understand these principles to adequately respond to changes in the way we relate to work.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles