The Impact of Artificial Intelligence - Widespread Job Losses

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence - Widespread Job Losses

- Last Updated: April 19, 2025

Calum McClelland

- Last Updated: April 19, 2025

In schools, the impact of artificial intelligence and automation is often portrayed in a good light. Think back to learning about the water wheel, mills, printing presses, steam engines, and assembly lines. Often, the underlying narrative is that these were great innovations that reduced the burden of labor on humans. However, the technological advances of our time seem to be less well-received. Perhaps it is because of our proximity to these examples of automation. Our closeness prevents us from seeing only the benefits and instead pushes us to see how much our lives and livelihood will be impacted by artificial intelligence.

McKinsey & Company reckons that, depending upon various adoption scenarios, automation will displace between 400 and 800 million jobs by 2030, requiring as many as 375 million people to switch job categories entirely. How could such a shift not cause fear and concern, especially for the world’s vulnerable countries and populations?

The Brookings Institution writes of a "new" kind of automation with more advanced robotics and AI that can bring work displacement to college graduates and professionals as much as it has to vehicle drivers and retail workers.

With frightening yet like these, it's no wonder AI and automation keep many of us up at night.

“Stop Being a Luddite”

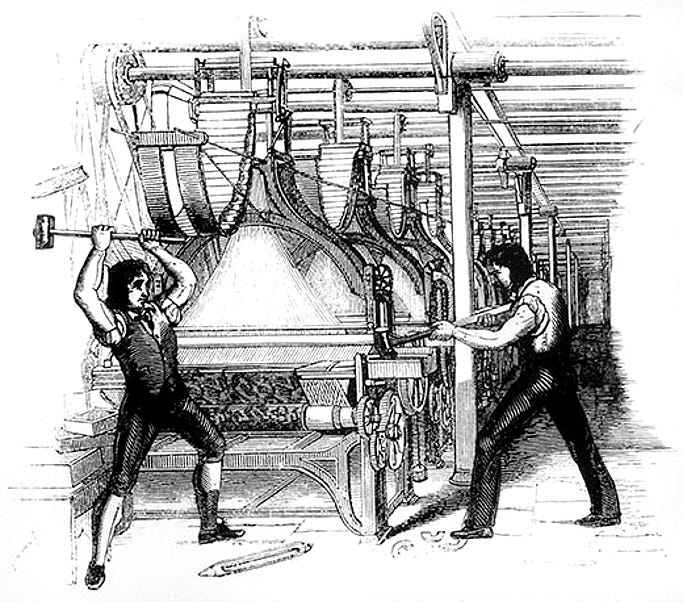

Although we may remember from our textbooks that the 19th century brought significant innovations to factories, this does not mean that it was welcomed with open arms by the people then. The Luddites were textile workers who protested against automation, eventually attacking and burning factories because “they feared that unskilled machine operators were robbing them of their livelihood.” The Luddite movement occurred all the way back in 1811, so concerns about job losses or job displacements due to automation are far from new.

When fear or concern is raised about the potential impact of artificial intelligence and automation on our workforce, a typical response is thus to point to the past; the same concerns are raised time and again and prove unfounded.

In 1961, President Kennedy said, “the major challenge of the sixties is to maintain full employment at a time when automation is replacing men.” In the 1980s, the advent of personal computers spurred “computerphobia” with many fearing computers would replace them.

Frame Breaking — The Luddites

So what happened?

Despite these fears and concerns, every technological shift has ended up creating more jobs than were destroyed. When particular tasks are automated, becoming cheaper and faster, you need more human workers to do the other functions in the process that haven’t been automated.

“During the Industrial Revolution, more and more tasks in the weaving process were automated, prompting workers to focus on the things machines could not do, such as operating a machine, and then tending multiple machines to keep them running smoothly. This caused output to grow explosively. In America during the 19th century, the amount of coarse cloth a single weaver could produce in an hour increased by a factor of 50, and the amount of labour required per yard of cloth fell by 98 percent. This made cloth cheaper and increased demand for it, which in turn created more jobs for weavers: their numbers quadrupled between 1830 and 1900. In other words, technology gradually changed the nature of the weaver’s job, and the skills required to do it, rather than replacing it altogether.”

-The Economist, Automation and Anxiety

Impact of Artificial Intelligence — A Bright Future?

Looking back on history, it seems reasonable to conclude that fears and concerns regarding AI and automation are understandable but ultimately unwarranted. Technological change may eliminate specific jobs, but it has always created more in the process.

Beyond net job creation, there are other reasons to be optimistic about the impact of artificial intelligence and automation.

“Simply put, jobs that robots can replace are not good jobs in the first place. As humans, we climb up the rungs of drudgery — physically tasking or mind-numbing jobs — to jobs that use what got us to the top of the food chain, our brains.”

-The Wall Street Journal, The Robots Are Coming. Welcome Them.

By eliminating the tedium, AI and automation can free us to pursue careers that give us a greater sense of meaning and well-being. Careers that challenge us, instill a sense of progress, provide us with autonomy, and make us feel like we belong; all attributes of a satisfying job.

And at a higher level, AI and automation will also help to eliminate disease and world poverty. Already, AI is driving great advances in medicine and healthcare with better disease prevention, higher accuracy diagnosis, and more effective treatment and cures. When it comes to eliminating world poverty, one of the biggest barriers is identifying where help is needed most. The AI and Global Development Lab is recreating historical and geographical human-development trajectories from satellite images starting from 1984 to measure poverty and the effects of foreign aid.

Impact of Artificial Intelligence — A Dark Future

I am all for optimism. But as much as I’d like to believe all of the above, this bright outlook on the future relies on seemingly shaky premises. Namely:

- The past is an accurate predictor of the future.

- We can weather the painful transition.

- There are some jobs that only humans can do.

The Past Isn’t an Accurate Predictor of the Future

As explored earlier, a common response to fears and concerns over the impact of artificial intelligence and automation is to point to the past. However, this approach only works if the future behaves similarly. There are many things that are different now than in the past, and these factors give us good reason to believe that the future will play out differently.

In the past, the technological disruption of one industry didn’t necessarily mean the disruption of another. Let’s take car manufacturing as an example; a robot in automobile manufacturing can drive big gains in productivity and efficiency, but that same robot would be useless trying to manufacture anything other than a car. The underlying technology of the robot might be adapted, but at best that still only addresses manufacturing

AI is different because it can be applied to virtually any industry. When you develop AI that can understand language, recognize patterns, and problem-solve, disruption isn’t contained. Imagine creating an AI that can diagnose diseases and handle medications, address lawsuits, and write articles like this one. No need to imagine: AI is already doing those exact things.

Another important distinction between now and the past is the speed of technological progress. Technological progress doesn’t advance linearly, it advances exponentially. Consider Moore’s Law: the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles roughly every two years.

In the words of University of Colorado physics professor Albert Allen Bartlett, “The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.” We drastically underestimate what happens when a value keeps doubling.

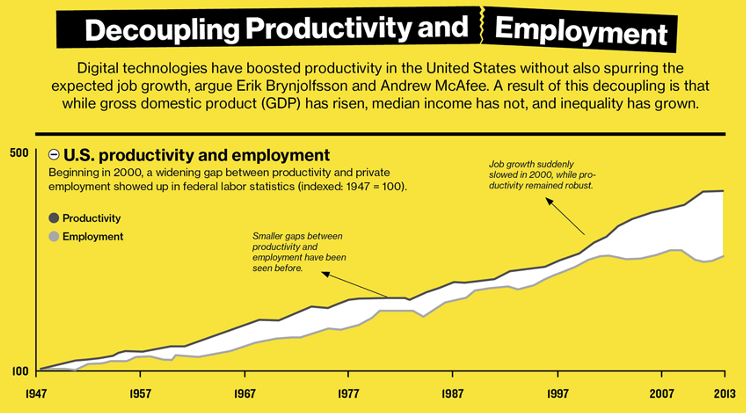

What do you get when technological progress is accelerating and AI can do jobs across a range of industries? An accelerating pace of job destruction.

“There’s no economic law that says ‘You will always create enough jobs or the balance will always be even’, it’s possible for a technology to dramatically favour one group and to hurt another group, and the net of that might be that you have fewer jobs.”

-Erik Brynjolfsson, Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy

In the past, yes, more jobs were created than were destroyed by technology. Workers were able to reskill and move laterally into other industries instead. But the past isn’t always an accurate predictor of the future. We can’t complacently sit back and think that everything is going to be ok.

This brings us to another critical issue ...

The Transition Will Be Extremely Painful

Let's pretend for a second that the past actually will be a good predictor of the future; artificial intelligence will impact some jobs but more jobs will be created to replace them. This brings up an absolutely critical question, what kinds of jobs are being created, and what kinds of jobs are being destroyed?

“Low- and high-skilled jobs have so far been less vulnerable to automation. The low-skilled jobs categories that are considered to have the best prospects over the next decade — including food service, janitorial work, gardening, home health, childcare, and security — are generally physical jobs, and require face-to-face interaction. At some point, robots will be able to fulfill these roles, but there’s little incentive to robotize these tasks at the moment, as there’s a large supply of humans who are willing to do them for low wages.”

-Slate, Will robots steal your job?

Blue-collar and white-collar jobs will be eliminated—basically, anything that requires middle skills (meaning that it requires some training, but not much). This leaves low-skill jobs, as described above, and high-skill jobs that require high levels of training and education.

There will assuredly be an increasing number of jobs related to programming, robotics, engineering, etc. After all, these skills will be needed to improve and maintain the AI and automation being used around us.

But will the people who lost their middle-skilled jobs be able to move into these high-skill roles instead? Certainly not without significant training and education. What about moving into low-skill jobs? Well, the number of these jobs is unlikely to increase, particularly because the middle class loses jobs and stops spending money on food service, gardening, home health, etc.

The transition could be very painful. It’s no secret that rising unemployment has a negative impact on society; less volunteerism, higher crime, and drug abuse are all correlated. A period of high unemployment, in which tens of millions of people are incapable of getting a job because they simply don’t have the necessary skills, will be our reality if we don’t adequately prepare.

So how do we prepare? At the minimum, by overhauling our entire education system and providing means for people to re-skill.

To transition from 90 percent of the American population farming to just 2 percent during the first industrial revolution, it took the mass introduction of primary education to equip people with the necessary skills to work. The problem is that we’re still using an education system that is geared toward the industrial age. The three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic) were once the important skills to learn to succeed in the workforce. Now, those are the skills quickly being overtaken by AI.

For a fascinating look at our current education system and its faults, check out this video from Sir Ken Robinson:

[embed]https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity?language=en[/embed]

In addition to transforming our whole education system, we should also accept that learning doesn’t end with formal schooling. The exponential acceleration of digital transformation means that learning must be a lifelong pursuit, constantly re-skilling to meet an ever-changing world.

Making huge changes to our education system, providing means for people to re-skill, and encouraging lifelong learning can help mitigate impact of artificial intelligence, but is that enough?

Are We F*cked? Will All Jobs Be Eliminated?

When I originally wrote this article a couple of years ago, I believed firmly that 99 percent of all jobs would be eliminated. Now, I'm not so sure. Here was my argument at the time:

The claim that 99 percent of all jobs will be eliminated may seem bold, and yet it’s all but certain. All you need are two premises:

- We will continue making progress in building more intelligent machines.

- Human intelligence arises from physical processes.

The first premise shouldn’t be at all controversial. The only reason to think that we would permanently stop progress, of any kind, is some extinction-level event that wipes out humanity, in which case this debate is irrelevant. Excluding such a disaster, technological progress will continue on an exponential curve. And it doesn’t matter how fast that progress is; all that matters is that it will continue. The incentives for people, companies, and governments are too great to think otherwise.

The second premise will be controversial, but notice that I said human intelligence. I didn’t say “consciousness” or “what it means to be human." That human intelligence arises from physical processes seems easy to demonstrate: if we affect the physical processes of the brain we can observe clear changes in intelligence. Though a gloomy example, it’s clear that poking holes in a person’s brain results in changes to their intelligence. A well-placed poke in someone’s Broca’s area and voilà—that person can’t process speech.

With these two premises in hand, we can conclude the following: we will build machines that have human-level intelligence and higher. It’s inevitable.

We already know that machines are better than humans at physical tasks, they can move faster, more precisely, and lift greater loads. When these machines are also as intelligent as us, there will be almost nothing they can’t do—or can't learn to do quickly. Therefore, 99 percent of jobs will eventually be eliminated.

But that doesn't mean we'll be redundant. We'll still need leaders (unless we give ourselves over to robot overlords) and our arts, music, etc., may remain solely human pursuits too. As for just about everything else? Machines will do it—and do it better.

“But who’s going to maintain the machines?” The machines.

“But who’s going to improve the machines?” The machines.

Assuming they could eventually learn 99 percent of what we do, surely they'll be capable of maintaining and improving themselves more precisely and efficiently than we ever could.

The above argument is sound, but the conclusion that 99 percent of all jobs will be eliminated I believe over-focused on our current conception of a "job." As I pointed out above, there's no guarantee that the future will play out like the past. After continuing to reflect and learn over the past few years, I now think there's good reason to believe that while 99 percent of all current jobs might be eliminated, there will still be plenty for humans to do (which is really what we care about, isn't it?).

"The one thing that humans can do that robots can’t (at least for a long while) is to decide what it is that humans want to do. This is not a trivial semantic trick; our desires are inspired by our previous inventions, making this a circular question."

-The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, by Kevin Kelly

Perhaps another way of looking at the above quote is this: a few years ago I read the book Emotional Intelligence, and was shocked to discover just how essential emotions are to decision-making. Not just important, but essential. People who had experienced brain damage to the emotional centers of their brains were absolutely incapable of making even the smallest decisions. This is because, when faced with a number of choices, they could think of logical reasons for doing or not doing any of them but had no emotional push/pull to choose.

So while AI and automation may eliminate the need for humans to do any of the doing, we will still need humans to determine what to do. And because everything that we do and everything that we build sparks new desires and shows us new possibilities, this "job" will never be eliminated.

If you had predicted in the early 19th century that almost all jobs would be eliminated, and you defined jobs as agricultural work, you would have been right. In the same way, I believe that what we think of as jobs today will almost certainly be eliminated too. But this does not mean that there will be no jobs at all, the "job" will instead shift to determining, what do we want to do? And then working with our AI and machines to make our desires a reality.

Is this overly optimistic? I don't think so. Either way, there's no question that the impact of artificial intelligence will be great and it's critical that we invest in the education and infrastructure needed to support people as many current jobs are eliminated and we transition to this new future.

Originally published on April 1, 2017. Updated on January 30, 2023.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles