Anatomy of a Smart City (Part I)

Anatomy of a Smart City (Part I)

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Susan Morrow

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

The time has come to write down a definition of what a smart city is. Like its forebears, the smart city now has the drivers in place to become a reality. The cities that grew out of the Neolithic agricultural revolution and then later the industrial revolution were driven by similar forces : increased population and technological advances that facilitated and drove a change in living conditions. The modern city has these same drivers but on a much larger scale. The global population, as mentioned earlier, is growing exponentially and we need ways of dealing with it.

The pressure of population on resources is a major driver to smarten up our current city models. And the technology to do so is finally here in the form of hyper-connectivity, improved and cheaper sensors, artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics. The clue here is in the data—the new energy in the modern smart city.

Data, or rather the analysis and application of these data, will be the pivot upon which the smart city turns. And much of these data will be our data, yours and mine, our personal information about who we are, what we do and perhaps why we do it. But before delving into that , what constitutes a smart city?

A smart city is like any other city. It's peopled by the Homo sapiens who live in it, others who commute to and from it and others still who simply visit on occasion. It has buildings for work, leisure and living. It has hospitals, commercial buildings, shops, car parks, public transport and private transport. It has everything we already use in a city. But the difference is in how the people, places and operations of the city interact and deliver their objectives.

A smart city can be described with a biological analogy, with each part impacting the others. In a biological system, you have groups of organs that work together to perform bodily functions, e.g. the digestive system. The organs communicate with each other using various mechanisms such as hormones or electrical signals to perform necessary functions. Overall, various systems work to create a fully functioning organism. A smart city is somewhat like a suite of biological systems, working separately to perform functions but acting as a whole to create an optimized environment for its human inhabitants.

Next in the series on smart city privacy is an introduction, using a biological analogy, to the composition a smart city—from health and home to governance.

Smart City Healthcare

A healthy population is a happy and productive one. Healthcare is an essential part of a resilient city. As our population grew after the agricultural revolution and moved into settlements, we saw an increase in communicable diseases like measles. Modern medicine has helped ameliorate communicable diseases such as smallpox, but other diseases based on poor western lifestyles, such as diabetes II, have reared their head and are now taking center stage.

Smart cities offer a number of ways to keep the population healthy. They do so by using an integrated approach to medicine , starting with the patient and patient-generated data. Data is the key to improving patient outcomes and communicating, analyzing and managing these data is part of the innovation of a smart city. Smart city digital healthcare is required to connect up all of the health data dots to allow practitioners to provide better direct care and improve medicine in general.

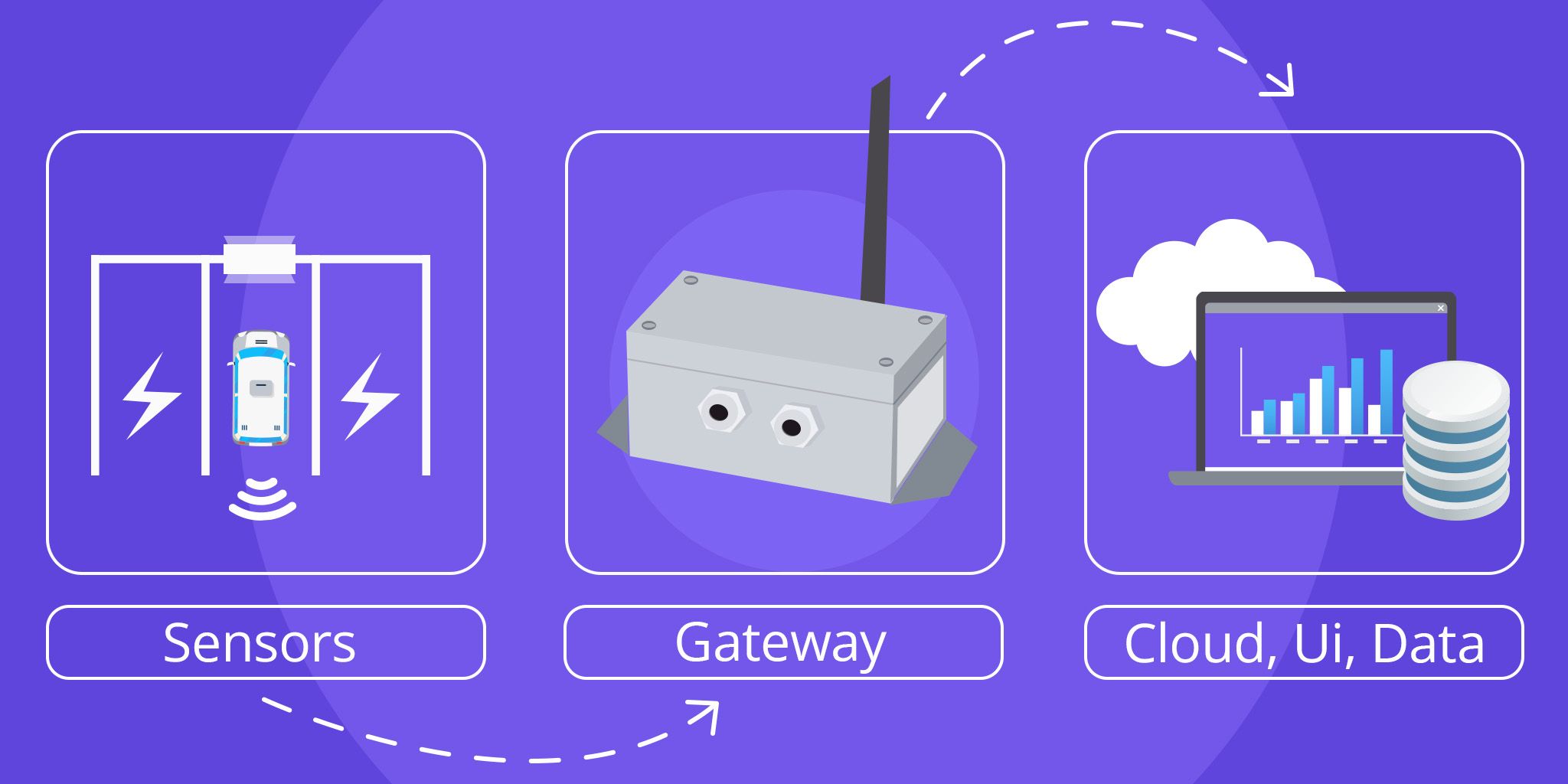

Smart healthcare is highly inclusive; it's an end-to-end experience that fully incorporates the patient into the service. This can only be achieved by using technologies such as Internet-connected devices, the Internet of Things (IoT), sensors and big data analysis, including machine learning and ultimately AI and robots. The data generated, either by the patient directly or by the healthcare service, is used to diagnose and find optimized treatments using modern medicine.

We are seeing progress in this area outside of full-blown smart cities. The market for digital health and health data is expected to be worth over $200 billion USD by 2020. The dots that need to be connected up are emerging:

- Smart wearables . These are already a successful health commodity; the market is expected to reach $14.4 billion USD by 2022. In the U.S. the FDA has already begun the process for connecting the digital health dots needed for a smart city by fast-tracking digital health products to encourage innovation in the area,

- Health apps. The UK government, for example, has found that in the UK, connected devices are being increasingly used and 57 percent of users share these health data with their primary physician. Health apps that do the job of sophisticated medical devices are here and include devices such as a portable smartphone ultrasound device.

- Remote medical treatment. The ability to easily share patient-generated data in real-time will allow hospitals to offset patient care into the community and their own homes more easily.

- Unification/analysis of patient data. Building a healthcare system that works across all aspects of the service seamlessly can be done by managing the full lifecycle of care. Systems such as Moscow’s Unified Medical Information and Analytical System (UMIAS) has been designed to interface across healthcare services, collecting patient data, offering remote patient monitoring, analyzing information and managing emergency care.

Smart city healthcare truly comes about when the parts that make up digital medicine are connected as a whole system.

Home

Home is where the heart is, but it's also where we create rich data that the smart city can use. The smart city home is part of the fabric of the city. It's the front line of our interactions with the city. We're already delving into the edges of the smart city when we buy our digital assistants, like Google Home or Amazon Alexa. And, virtual reality (VR) devices are expanding the types of data collected within the home environment with the addition of “body movement tracking data” to the personal data collected.

Smart living is something we have always strived for since we discovered fire to warm our living area and cook our food. The development of any technology usually finds its way into our domestic lives ; electricity lit our homes and the telephone connected us to other homes. Smart homes are taking our use of technology to a new level. In doing so, it offers to make energy use more efficient and communications more effective.

Our homes are likely to be mini-hubs for smart city living, each home unit being part of a larger "smart hive." Connected living will integrate with other areas of smart living such as healthcare. The data generated in our daily lives can be used to optimize our energy use and make our living conditions more efficient and comfortable using an array of smart devices and grids connecting us to the wider smart city services.

Probably more than any other area of the smart city, the smart home is the interface between human and machine. The connected home will also expand the range of the smart city. Homes outside the boundaries of the smart city can become satellites of the city by linking into the city using connected devices. The reach of smart, connected technology that extracts and analyzes personal data from within our very homes has, as expected, been a central point of privacy concerns. An Austrian study into the attitudes towards smart energy devices in homes found that although there was a feeling of general trust towards energy providers, there was concern around the privacy and security of the data management

In Anatomy of the Smart City (Part II), the next post in this series on smart city privacy, we will examine more aspects of the fundamental structures that make up a smart city.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

IoT in 2026: Trends and Predictions

Related Articles