Protecting Your Privacy in an IoT-Connected World

Protecting Your Privacy in an IoT-Connected World

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Amanda Lopez

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Can we protect privacy in an IoT-connected world? Let's first compare face-to-face privacy with online Privacy and Trust, trace their evolution, then explore IoT privacy connections and how mobile phone data is used.

Privacy is a very personal thing. This simple fact gets complex really fast. Think about it: We often share more with the people we trust. My own risk tolerance for sharing personal information with somebody face-to-face may be completely different from yours, and my tolerance level may change over time.

This 'user-defined limit' to data sharing—revealing personal information, history, thoughts, and feelings—is usually based on one's trust in a system (or person) and its privacy settings (or likelihood to gossip). Privacy and Trust in the applications and devices we use also changes over time. When Facebook let us protect our data using privacy settings, we defined new limits for displaying that data and trusted Facebook to protect it going forward.

The Evolution of Privacy & Trust

Privacy and Trust both factor into our laws and societal norms. In the 1980s, we lived more anonymous lives. Even though the police could access a person’s name, address, phone number and license, our personal information was not commonly available to the public. Today our data can become a commodity for marketers, a likely vote for politicians, or a statistic for data scientists.

Our privacy laws protect our personally identifiable information (PII) for good reason; our personal data may unlock the door to our identity, finances, and more. These days PII is often published online next to photos, life events, bank balances, property records, credit history, resume, health status, family tree, friends, schools, hobbies and politics.

Our tolerance for trusting sites with our data has changed over time. In an open society like ours, online Trust is rewarded. Craigslist and online dating bring strangers into our lives. Airbnb and Couchsurfing sites bring strangers into our homes. Opening up to strangers gradually becomes normalized behavior, especially for our youth.

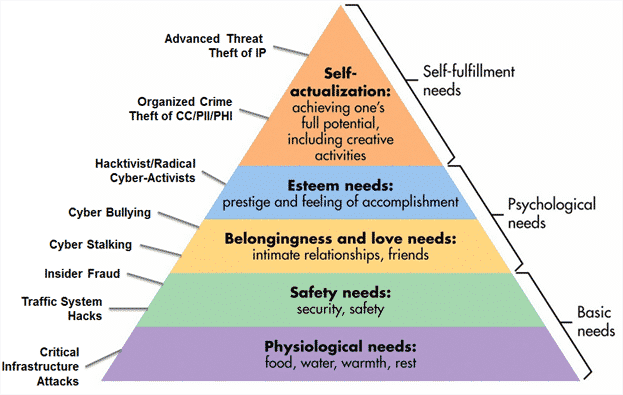

Even so, no matter what our needs are, we must constantly weigh the benefits of trusting others with the risks of revealing our private data. James Robinson offers a unique Mapping of Cyber Attacks to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Image Credit: Simple Psychology

Connecting Privacy to IoT

Similar to personal relationships, Trust governs how we control Privacy in our IoT environments. As IoT devices become more connected, more data is shared between people, companies, governments and ecosystems.

Sensors, devices, data, machines and cloud connections rely heavily on established trust relationships. Connecting more types of IoT devices (i.e., adding intrusion points) increases the threat surface of a given system, thereby increasing the overall security risk. Without the ability to limit privacy settings, it's difficult to establish trust with an IoT system or device.

Security is traditionally a challenge for many device manufacturers speeding toward early adoption of their IoT products. Without automatic security updates, 2-factor authentication, or laws promoting security protection, many IOT devices will continue to present security risks.

The Mobile Phone as Tracking Device

Let’s look at the mobile phone as a tracking device. It tracks our location and verifies our identity and password in 2-factor authentication. Phone tracking offers us real-time benefits, such as mobile:

- Traffic reports to avoid accidents on our route

- Alerts for friends in our vicinity

- In-store coupons for nearby stores

Marketers and mobile phone companies use our real-time location to:

- Offer marketing that is specific to our interests

- Understand the popularity of businesses or events to different users

- Provide improved mobile reception (e.g., Sprint would move its signal-boosting trailer to Nascar events to improve phone call quality)

The Mobile Phone as Home Invasion Tool

Ironically, because our mobile phone acts like a tracking device, hackers can use our mobile phone's location data to steal from us, harm us, or at the very least learn our daily routines and patterns. For example, if I post recognizable photos of my vacation spot to Facebook, thieves know I’m not at home and that’s one less thing to worry about.

Many IoT devices connect digitally to mobile phones, that is, they often share data and access via the mobile device itself. For example, Smart Home IoT products have alarm systems that can be remotely accessed via smartphone apps. Burglars can use this stolen data to know when to break into homes while residents are away.

The Mobile Phone as an IoT Security Mechanism

Fahmida Rashid’s article entitled “Secure Your (Easily Hackable) Smart Home” explains how to make your connected home more secure. Tom’s Guide also notes that “the newly revealed KRACK vulnerability leaves nearly all Wi-Fi networks at risk.”

As with humans, we need to constantly weigh the benefits of trusting IoT products (such as sensors, devices, and machines) with the risks of revealing that private data online. In the digital world, when data is released 'into the wild' we have almost no control over who accesses that data or for what purpose it will be used.

Privacy is a very personal thing. This simple fact gets complex really fast.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles