Smart City Privacy : Our Past, Who We Are and Why We Live This Way

Smart City Privacy : Our Past, Who We Are and Why We Live This Way

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Susan Morrow

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

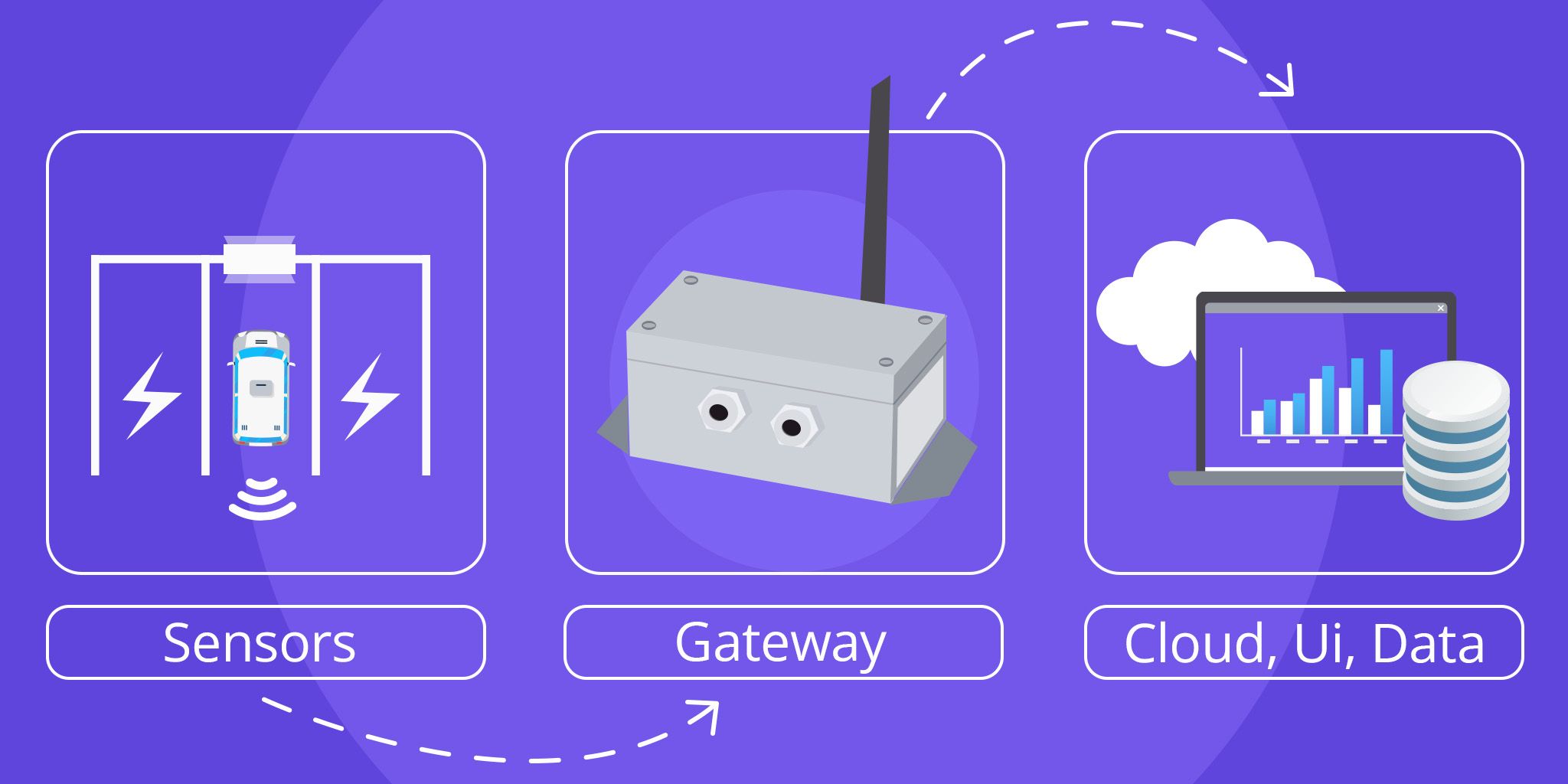

In a series of posts, I will talk about the concept of a "smart city" and the privacy implications of living in such an environment. To build up a picture of what the privacy implications of smart living are, I will look back at how human beings came to live in cities in the first place. As we move into a near-future where data and the Internet of Things (IoT) will run our cities, looking back to look forward may help us design better places to live.

I will start at almost the beginning, at the earliest days of sedentary civilisation. Knowing why we built cities may help us to build better, truly smarter cities, now.

Looking Smart

Looking back gives us time to reflect, and knowing the path we took to get to a place can give us a feel for why we wanted to be there in the first place. Human beings are animals first and foremost, and as animals, we have certain drivers that push us forward in our lives. The fundamental evolutionary driver of life is reproduction; the rest of the things we chose to do around this are packaged to make reproduction successful. This usually translates into control of our resources, which include food, mates, and protection against the elements. Of course, in the wider world of humans, we also have many cultural and social overlays on top of these evolutionary drivers.

Not all of us want children, nor do we all have children, but we all still want to be warm, have food in our bellies, feel safe and have purpose. Human beings have strive to find all these things, and in doing so, our societies have tended toward bringing our species together into groups. Over time, these groups expanded; from a village grows a town, from a town grows a city. Over time, we've made our cities fit for those purposes of safety, sustenance, and purpose in a myriad ways. The smart city is the next generation's attempt to optimize this ongoing movement.

Before exploring the smart city, let's take a little time to walk the path of our elders and see the city through their eyes . Perhaps we will see that we have the same goals but different methods of achieving them . Perhaps we will also see that the privacy need intrinsic in our being was the same then as it is now, and perhaps we will begin to understand why this intrinsic need has to be carried over into the smart cities we will build in our near future.

Evolving Cities

This isn't a treatise about origins, but it will draw on where we've been. We have to step back to an earlier place in our history to work forward, and this place is the agricultural or neolithic revolution. Before this revolution, human beings found their food and other resources by hunting and gathering. Hunting and gathering is a good system, still in existence today in some societies. But it's a limiting system. Hunting and gathering can only provide food for small group sizes. Various studies have been carried out to estimate the optimal size of a group supported by this mode of subsistence. Biologist Richerson estimates the group size, able to be supported under hunter-gatherer conditions, varies depending on the ecology. Richerson states,

"Not only were the densities of most hunters and gatherers low, but typical settlement sizes are also small." — Richerson, "Hunting and Gathering Societies."

Hunting and gathering of food fed Homo sapiens and earlier hominid ancestors for around 2.5 million years. Then a shift happened; cold winds came, warm winds took over and the available food changed. Instead of moving with the food in the hunt, we found ways of making the food come to us: we discovered agriculture.

"Our species, man in the widest sense, has succeeded in surviving and multiplying chiefly by improving his equipment for living." — Gordon Childe, What Happened in History, 1942.

Childe continued, stating how human beings, unlike other animals, create their own non-natural equipment. He said:

"Man has very little equipment of this sort and has discarded some that he started with during prehistoric tunes. It is replaced by tools, extracorporeal organs that he makes, uses, and discards at will; he makes picks and shovels for digging, weapons for killing game and enemies, adzes and axes for cutting wood, clothing to keep him warm in cold weather, houses of wood, brick, or stone to provide shelter." — Gordon Childe, What Happened in History, 1942.

The actual root cause of the shift to a sustainable way of living using agriculture has had many theories and continues to be debated. One thought postulated by Childe was that climate change, bringing dry conditions, forced humans into oases where experimentation with seeds produced domestication. Other theories postulate that naturally increasing populations at the time of the shift put pressure on the wild food supplies.

However, the neolithic revolution with agriculture was unlikely to be a sudden event. More likely, it was a long, drawn-out process of experimentation, with seeds being gardened' as opposed to farmed. Long periods of experimentation with plants created hybrids that had the right mix of robustness with digestible matter. The causes of the neolithic revolution and the resulting shift from hunter-gathering methods to domestication of plants and animals meant human beings could do one thing that would change everything : they could control their food source.

So what, you may say. Wouldn't that just mean they had to work harder to make sure they had food supplies? Wouldn't they need also to have the right tools and the right soil and so on? The answer is of course, yes, and this is all part of the driving force into the city.

Agriculture allowed human beings to be still. They no longer had to follow the herd across the plains or spend most of the day gathering berries and seeds. Instead, they could create a more fixed abode—a sedentary lifestyle that opened up new ways of living and working.

Agriculture, however, may come back to haunt us in the modern smart city…

Watch for my next post, titled: The First Smart City.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Navigating the Future of Embedded Computing

Related Articles